Confessional Conflicts in Europe

The Reformation ushered in a period of conflict that would produce not merely impassioned debate of theological precepts but also murderous violence and finally war.

In the Reformation era, every emerging Protestant denomination along with the Catholic Church believed in one exclusive religious Truth—each of their versions of that truth was different from every other. This conviction was hardly conducive to peace. The Reformation ushered in a period of conflict that would produce not merely impassioned debate of theological precepts but also murderous violence and finally war. Only with the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, which ended the Thirty Years’ War in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, was the futility of compulsion acknowledged. Even then, Anabaptists, Spiritualists, Jews, and Anti-Trinitarians were not accorded the privilege of freedom from persecution that, officially, Catholics, Lutherans, and Reformed Christians enjoyed. A recent interpretation of the Reformation by Nicholas Terpstra has seen nearly every region and territory as determined to root out recusancy (refusal to adhere to the established church) and as casting sizable populations into refugee status. The rulers of the sixteenth century were, in short, intent on the purification of the body of those residents who were subject to them. Toleration was hardly a moral virtue or a social ideal. Where it appears to have existed, it was likely a pragmatic forbearance.

Efforts to force recantation or to reconcile opposed theological positions were incessant. The forums of such attempts ranged from personal meetings to formally organized disputation, imperial diets, and ecclesiastical synods. Whereas the Diet of Worms of 1521 revealed that under no circumstances would Martin Luther submit to the dictation of the Catholic Church, the Marburg Colloquy of 1529, hosted by Landgrave Philipp of Hesse, showed that the most committed new reformers of European religion would not accommodate one another in their definitions of what occurred during the Eucharist (or Lord’s Supper). Huldrych Zwingli wept as their attempts failed, and Luther ranted. Martin Bucer thought he had found a solution in the shaded wording of the Wittenberg Concord of 1536, but he had not. The Colloquy of Regensburg of 1541 was designed to reconcile Catholics and Lutherans, but it, too, quickly went down to defeat, paving the way for the War of the League of Schmalkald of 1546-1547, a portent of religious wars to come.

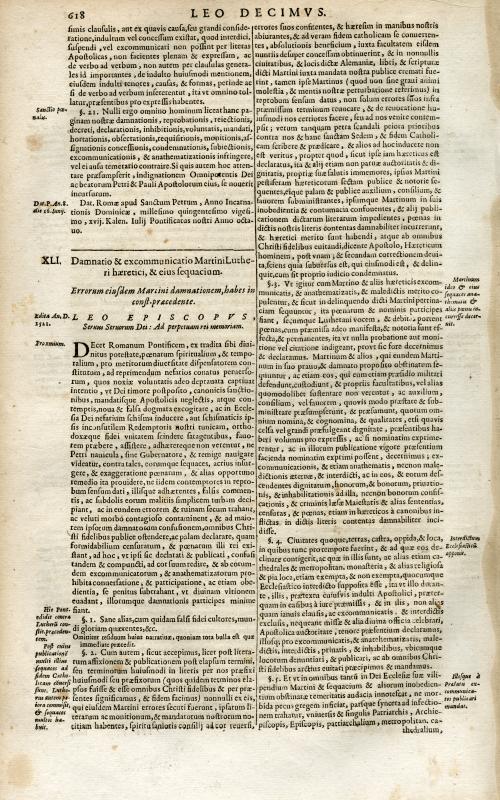

Papal Bull, June 16, 1521, Magnvm bvllarivm Romanvm. In this document Martin Luther is officially excommunicated as a heretic from the Catholic Church.

The widow queen-regent of France, Catherine de’ Medici, strove mightily to fend off religious violence in France that might, in fact, undermine her sons’ dynastic hold on the throne. She took measures to reconcile opposing sides, Catholic and Reformed (Huguenot) at the Colloquy of Poissy in 1561. Neither side would make concessions to the other. The Guise-led massacre of worshipping Huguenots at Vassy the following year marks the beginning of the French Wars of Religion for modern historians. This civil war would continue intermittently for the next 36 years, leaving a legacy of hatred that neither side could suppress.

During the same decade in the Low Countries, Calvinists met with refusal the categorical demand of their king, Philipp II of Spain, that they return to Holy Mother Church. Some expressed their rejection of his autocratic methods, as well as the offense they took at Catholic “idolatry,” by taking part in a wave of iconoclasm, the Beeldenstorm of 1566. Similar outbursts had occurred or would yet occur in parts of Germany, Switzerland, France, and Scotland. Reformed theologians found religious statues and paintings to violate the prohibition of idol-worship contained in the Ten Commandments.

Historians name the ongoing violence of the second half of the sixteenth century in France and the Low Countries “wars of religion.” Despite the distinct political and economic elements that entered into this violence, religious differences aptly symbolized the principal and conscious sources of alienation. Studies of France have shown how alienating Catholics’ and Huguenots’ versions of the Eucharist were to one another: the one focusing on the presiding clergyman’s ability to cause the veritable presence of Christ’s flesh and blood (transubstantion), the other on Christ’s entirely spiritual nourishment of his elect. On the eve of Saint Bartholomew’s Day (August 24) in 1572, Catholics began to slaughter leading Huguenots who were gathered in Paris for a royal wedding. About 3,000 met grisly deaths in the capital, and in the immediate aftermath perhaps another 2,000 in the provinces. This massacre marked the beginning of Huguenot decline, despite Henry IV’s efforts at reconciliation. In the Low Countries in 1581, the seven northern provinces withdrew their allegiance from Philip II and formed their own new nation, the origin of The Netherlands. In the following century, similar wars, though often orchestrated by outsiders, would devastate parts of the Holy Roman Empire. One can argue that the English Civil War of 1642-1651, too, was in part a war of religion.

Throughout the century 1550-1650, theologians made repeated efforts to compose their differences, but they never abandoned their sense of alone possessing the Truth. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 finally recognized the legitimacy of Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism (Reformed). In the short term, however, other denominations found no peace. Some sought refuge in North America. Anti-Semitism persisted throughout the period.

To cite text:

Karant-Nunn, Susan, & Lotz-Heumann, Ute (2017). Confessional Conflict. After 500 Years: Print and Propaganda in the Protestant Reformation. University of Arizona Libraries.

Selected titles from University of Arizona Special Collections:

Silvestro Mazzolini (ca. 1456-ca. 1527) Modus solennis, Rome, 1553

Johann Friedrich I, Kurfurst von Sachsen (1503-1544). Der durchleuchtigst und durchleuchtigen, n.p., 1546

Antwort dem Murnar, n.p., 1523

Council of Trent (1545-1563). Decisiones et declarations illustrissimorum, Antwerp, 1615

John Foxe (1516-1587). A continuation of the histories of foreign martyrs, London, 1632