Women's Studies Activism & Social Change

“The increasing institutionalization of women’s studies has brought to the fore questions about the relationships of theory to practice and activism to scholarship.”

Kennedy and Beins[i]

Feminism’s focus on power and inequality has been linked to social changes since the early days of the contemporary women’s movement. On university campuses, women’s studies faculty assumed a leadership role in advocating for gender equality on campus, engaging in scholarship that guides policy decisions at a community and national level, and engaging the community in social change efforts.

Women's Studies brochure featuring its logo. SIROW Records(MS 518) UA Libraries, Special Collections

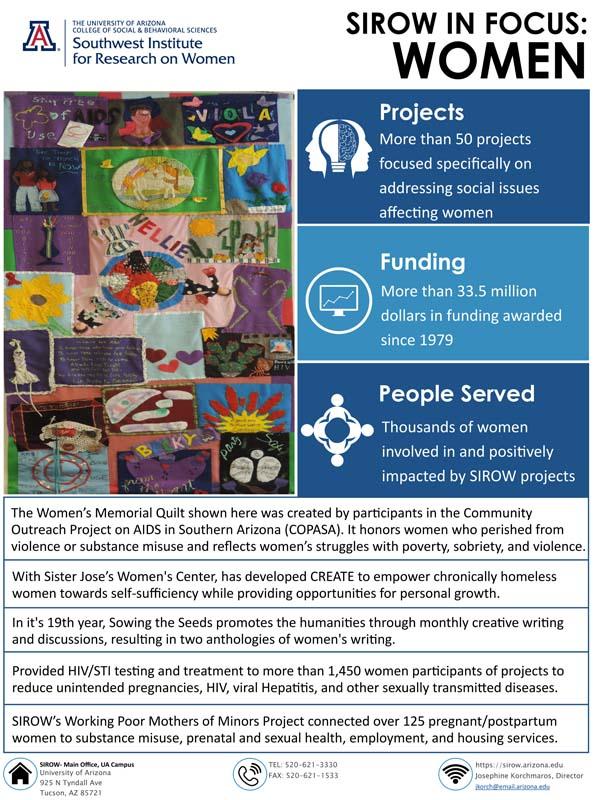

At the national level, The Southwest Institute for Research on Women (SIROW) and other women’s research centers created a National Council of Feminist Research Centers in 1981. In addition to sharing best practices and strategies, this group advocated for funding of research on women’s issues to support policy decisions.[ii]

At the state level, SIROW created reports on women’s issues organizations such as the Arizona Town Halls and Southern Arizona Women’s Foundation. The first Arizona Women’s Town Hall addressed Women and the Arizona Economy focusing on women’s contributions to the state’s economy and their position in the economy, connections between women’s home and family lives, and corporate and public policies that affect women’s economic condition.[iii] Subsequent reports focused on work, politics, economics, demographics and health.

Women’s Studies faculty wanted to amplify the voices of women in the community so they organized public talks by feminist scholars and activists, community action projects, and teacher education. In 1985, for example, SIROW created a University of Arizona Women exhibition in the Student Union Gallery to celebrate the UA Centennial. The exhibit featured representations of dorm rooms from 1895 and 1985, vintage photographs, letters, and newspaper articles.[iv] Over 100 people a day visited the exhibit in its month-long installation.

Poster created to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Southwest Institute for Research on Women's (SIROW) in 2019. Courtesy of Josephine Korchmaros, Director, SIROW.

Research by Women Studies faculty often served as the catalyst for community action projects. SIROW sponsored several research projects on widows in collaboration with faculty from the College of Nursing, under the leadership of Dr. Margarita Kay. Because the project Coping and Health among Older Urban Widows found that Mexican American women had less support from friends and social networks, the next project focused on the Efficacy of Support Groups for Mexican-American Widows.[v] Publicity about these projects encouraged community organizations to extend these services.[vi]

Women’s Studies’ commitment to introducing scholarship on women in public schools was recognized early. In 1977, the Feminist Press, in partnership with Women’s Studies, field tested three new publications for high school students in Tucson public schools. Workshops to encourage teachers to include materials on women began with the Institute for Equality in Education, funded by the Arizona Office of Education in 1978. Because this first institute worked with hundreds of teachers and reached 10,000 students, the project was extended in subsequent years to New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. Women’s Studies faculty’s leadership in teacher education was evident in their success in securing external funding over numerous years.[vii]

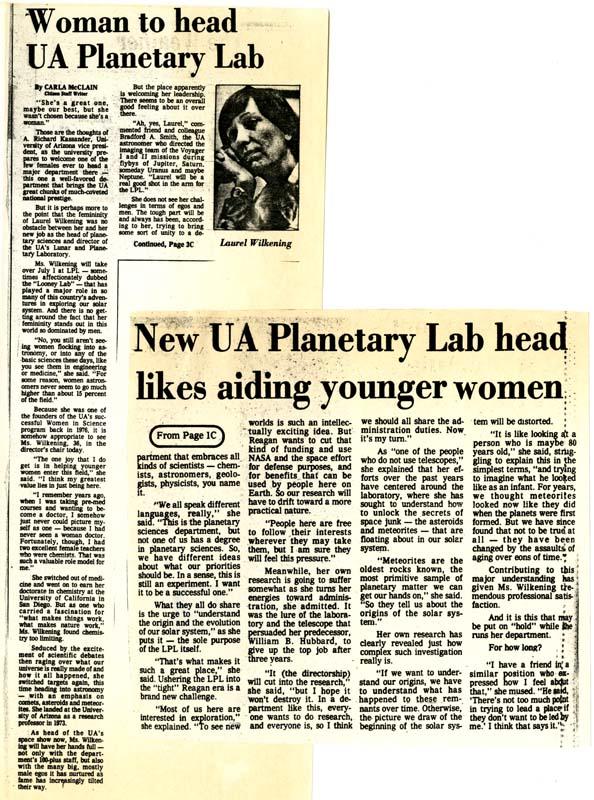

Dr. Laurel Wilkening, a founder of the Commission on the Status of University Women and its Task Force on Women’s Studies, also started the Women in Science and Engineering program (WISE). She began with an informal group that provided mentoring and career panels to encourage undergraduate women to pursue careers in science and engineering. In 1974 she obtained funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to present workshops; by 1977, 100 undergraduate women attended the third annual workshop. The UA was the only university in the country to be awarded NSF funding for three consecutive years. In 1979 Wilkening institutionalized WISE by asking for recognition of WISE as a university-wide committee that she chaired. Wilkening, a professor in Lunar and Planetary Sciences, was inspired by her own experiences:

I remember years ago, when I was taking pre-med courses and wanting to become a doctor, I somehow just never could picture myself as one–because I had never seen a woman doctor. Fortunately, though, I had two excellent female teachers who were chemists. That was such a valuable role model for me.[viii]

Over time, the career workshops began to focus on high school students and mentoring and career panels for undergraduate women. The synergy between research and activism is illustrated by Patricia MacCorquodale’s work on Mexican American women in science that revealed Mexican American families strongly supported education, but they lacked knowledge about college and careers.[ix] This finding led to designing parent sessions at the WISE annual workshops. WISE also began a long, successful collaboration with campus colleagues in math, science, and teacher education—Family Math and Family Science—that engaged families in learning activities.

In 1981, Women’s Studies faculty helped organize a new organization, the Association for Women Faculty (AWF), to replace the Commission on the Status of University Women. Their efforts resulted in a large pay equity study, the first parental leave policy for faculty (including stopping the tenure clock), and improved hiring of women. Because gender issues persisted, AWF pressured the university and Arizona Board of Regents (ABOR) to appoint a task force to conduct a comprehensive study of women’s issues. ABOR appointed a Commission on the Status of Women, referred to as the Millennium Commission, to report on gender based problems and make recommendations for changes to be accomplished by the year 2000.[x] The issues identified included pay equity, paucity of minority women, sexual harassment, childcare issues and sexuality; many of the issues continue in 2020.

Marilyn Heins, M.D. and faculty member in the College of Medicine, and Dorothy Finley, a well-known business owner, decided to organize community support for Women’s Studies to strengthen community leaders’ interest in and knowledge of women’s studies. In 1985 they founded the Women’s Studies Advisory Council (WOSAC). WOSAC engages the Tucson community in discussion of women’s issues and presentations of feminist research; they were instrumental in insuring support when proposals concerning Women’s Studies or SIROW came before ABOR. They also raise funds to support scholarships for graduate students, emergency funds for students, travel grants, and a research fellowship for faculty.

WOSAC’s largest project is the Women’s Plaza of Honor, a garden and gathering place on campus that “publicly and permanently celebrates women who have made significant contributions to the history of Arizona or have enriched the lives of others.”[xi] In 2005, Arizona Governor Janet Napolitano joined UA leaders, Women’s Studies faculty, and community members to inaugurate the plaza. Arches in the plaza honor African American women, first UA women administrators, inspirational women, Native American women, Southern Arizona women activists, women lawyers, and women of the 1540 Cibola Journey, the expedition of Spanish conquistador Francisco Vasquez de Coronado into Arizona. Women recognized in other features of the plaza range from UA faculty and alumni and community leaders to family members, teachers, babysitters, and friends who have touched women’s lives.

__________________________________________________________________