Suffrage Debates & Women's Rights

Arguments for and against women’s suffrage relied on beliefs about women’s nature and their role in society. In newspapers, in meeting halls, and across kitchen tables, debates raged about whether and how men and women were different. Arguments in support of suffrage were grounded in women’s rights:

- Natural rights—those who are affected by laws should have a say in making them

- No taxation without representation—women are wage workers and pay taxes

- Legislation will be more moral, educational and humane—women will clean up politics and government

Some suffragists made racist and exclusionary arguments that giving women the vote would increase the proportion of native-born voters or that white women would overcome the numbers of African American men added to voting registers by the 13th and 14th amendments.

Suffragists emphasized their femininity by marching in long white dresses, selling merchandise like cook books, dishes, paper dolls, coloring pages, fans, campaign buttons, women’s newspapers and magazines, singing suffrage songs, and carrying yellow flowers. Anti-suffragists adopted the red rose as their symbol.

Anti-suffrage arguments were strongly grounded in women’s domestic role:

- Women’s place is in the home—women should not be exposed to the corruption of politics

- Women will be unable to understand the issues—economics and politics are a man’s world

- Women don’t want to vote—only a few radical, masculine, dominant women want it

- Men are the head of the household—men’s votes cover women’s interests

A Bisbee, Arizona, woman commented in 1911, “Suppose suffrage were conferred upon women, what good would be accomplished by it? In ninety cases out of one hundred, wives would vote with husbands, sisters with brothers and the result would be the same.”[ii]

Women’s suffrage found support in the western territories.[iii] In 1869 Wyoming was the first state or territory to grant women suffrage; Colorado (1893), Utah (1896), and Idaho (1896) followed shortly. Why did politicians support women voting in the new territories and states?

- These new, emerging governments were more open to experiments and political reform.

- Men valued settler women’s hard work on homesteads, ranches and in emerging towns.

- The percentage of women who were widows or involved in wage work was higher than in the East.

- There was the lack of an organized opposition. The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was not organized until 1911; by then, six Western states had granted women the vote.

Arizona became a territory in 1863 when it separated from New Mexico. Between 1870 and 1880, the population quadrupled. By the 1880 census, there were 40,430 people with about two men for every woman.[iv] The vast majority of those counted were white (87 percent); Mexicans were not differentiated at this time. Chinese and “civilized Indians” represented four percent and 8.6 percent respectively.

In 1880, Tucson was the only city with more than 4,000 people. At the University of Arizona (UA), even though two women were members of the first graduating class in 1895, women enrolled in small numbers and few women were faculty. One faculty member from 1905, May Fish, described the university as “first of all for men.”[v] By the turn of the century, women were concerned about their place on campus and began to ask for equal rights. Georgiana Colton’s 1903 essay, “By Order of the Regents,” presented women’s anger about curfew hours and restrictions about where women could go on campus claiming, “We are shut up like prisoners, and not allowed to walk where we please, for fear we will see a boy.”[vi]

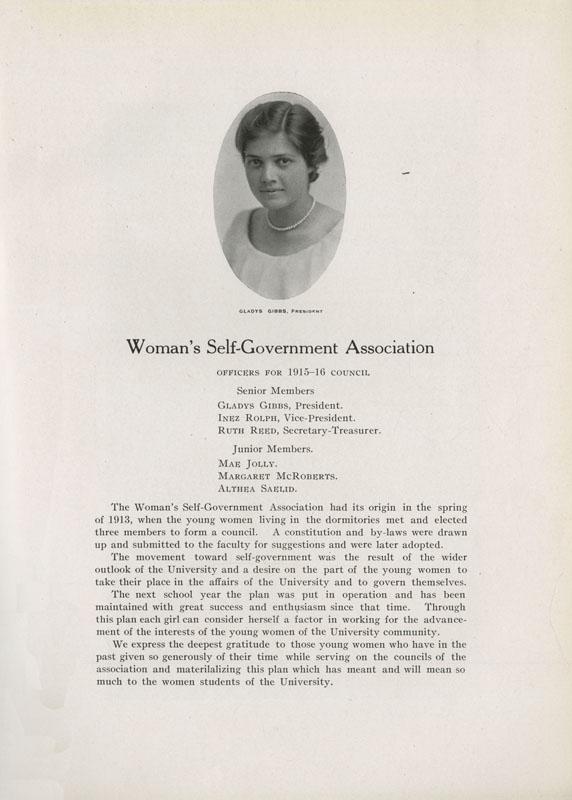

Women undergraduates organized several new organizations to expand their voice on campus and strengthen their community. The Women’s League, organized in 1909, sought “to promote social intercourse, to form friendships about the girls and to make the new ones feel at home.”[vii] They wrote to women entering the university to welcome them to campus and included women students living in Tucson and alumna in their activities. The Woman’s Self-Government Association, formed in 1913, had a different, empowering focus: “The movement toward self-government was the result of wider outlook of the University and a desire on the part of young women to take their place in the affairs of the University and to govern themselves.”[viii]

Women’s efforts to find and express their voice contrasted sharply with the dominant masculine culture. Jokes published in the UA yearbooks reinforced valuing women for their appearance and belittling their intelligence. Here are two examples related to voting from the 1915 Desert yearbook:[ix]

When arrested by a policeman an English suffragist cut the officer’s suspenders and made her escape while he was otherwise engaged.

Alice—“How are you going to vote, Inez?”

Inez—“Now, let me see. I think I’ll vote in my sealskin coat.”

Alice—“Well, that’s lovely.”

__________________________________________________________________