Scholarship By and About Women

"Until…the advent of contemporary feminist inquiry, scholarship has been too often gender blind in the negative sense of that term, assuming the masculine as the human norm, presupposing that what was true of men must be true of women too."

Susan Aiken et al.[i]

Women’s Studies faculty were excited about the new scholarship on women. As the field flourished, they formed a feminist theory group to discuss influential books and articles. They benefitted from meeting national scholars who came to campus to give lectures. As women’s studies became more institutionalized, departments began hiring faculty who were specialists in this field. Other faculty, who were teaching courses on women, began to ask questions about gender in their own research. By studying women’s lives and experiences, hearing women’s voices and perspectives, and including gender as a dimension in research, scholars began to formulate new questions and theories that fundamentally changed established knowledge. Women’s studies research also contributed to institutionalizing the program by framing women’s studies as a legitimate academic field, enhancing the national and international reputation of the faculty involved, and obtaining external funding.

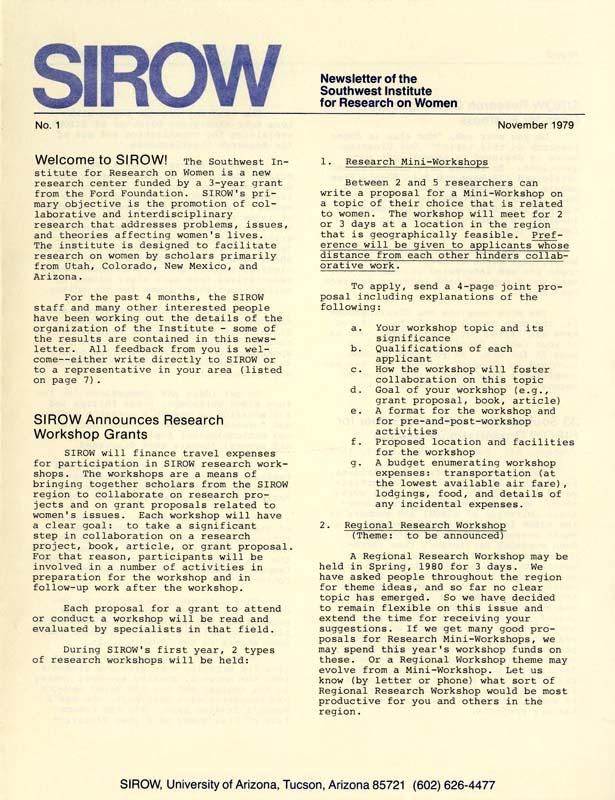

As women’s studies programs began to organize nationally, several programs created research centers focused on women. Myra Dinnerstein thought strategically about what the UA could offer in terms of research on women. She identified that the UA’s position as a public university in the Southwest gave it a unique contribution, a willingness to change, and greater diversity.[ii] These conversations resulted in the founding of the Southwest Institute for Research on Women (SIROW) at the University of Arizona in 1979 with a $200,000 grant from the Ford Foundation. SIROW’s goal was “the promotion of collaborative and interdisciplinary research that addresses problems, issues and theories affecting women’s lives.”[iii] The regional focus of SIROW was Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona, although some projects have included the western states and Mexican states along the US-Mexico border.

SIROW provided support and advice to scholars in the region, helping them succeed in getting funding for research and conferences and fostering collaboration within and across universities. Patricia MacCorquodale received the first SIROW research grant, “Social Influences on the Participation of Women in Science.”[iv] Under the leadership of Jan Monk (1980-2004), SIROW was highly successful in achieving external funding. As Monk noted, “All of our project money comes from outside. I figure we bring in about four times the money we get from the university. We’re a good investment.”[v] In 1981 SIROW reached $1 million in grants; by 1983 SIROW’s success came to $2.6 million. Since its inception in 1979, SIROW has helped to bring in close to $100 million in grants and contracts. More than 50 of SIROW's projects have focused specifically on addressing social issues affecting women, funded by more than $33.5 million in funding.

Women’s Studies faculty collaborated with SIROW leadership to bring a series of conferences to campus. Scholars from the SIROW region and the nation attended, and books and other publications frequently resulted from these conferences.

- Interdisciplinary conference on menopause, 1979. Publication: Changing Perspectives on Menopause[vi]

- Western Women: Their Lives—Their Land. 1984 conference and book.[vii]

- Daughters of the Desert: Women Anthropologists in the Southwest 1880-1980. 1986 conference and book.[viii]

- Sex Differences in Language, 1982. Publication: Language, Gender and Sex in Comparative Perspective.[ix]

- The Future of Women’s Studies: Foundations, interrogations, politics, 2000. Publication: Women’s Studies for the Future.[x]

The Desert Is No Lady book cover, SIROW Records (MS 518), UA Libraries, Special Collections

Infinite Divisions book cover, SIROW Records (MS 518), UA Libraries, Special Collections

Other SIROW collaborations resulted in new courses, books, even a film.

- The Rockefeller Foundation supported interdisciplinary project “Visions of Landscape: Women’s Writers and Artists in the Southwest, 1880-1980.” This research focused on how gender and ethnicity shape the aesthetic responses to the region. Subsequently, the project resulted in a film and book titled The Desert is No Lady: Southwestern Landscapes in Women’s Writing and Art.[xi]

- Tey Diana Rebolledo (University of New Mexico) and Eliana S. Rivero (UA) collaborated on Infinite Divisions: An anthology of Chicana literature, one of the first collections of Chicana writing.[xii]

- SIROW’s collaborations in the community on HIV/AIDS resulted in a new, interdisciplinary UA course on this topic.

Women’s Studies faculty became concerned that they were only reaching a small percentage of undergraduate students through Women’s Studies classes. A survey of undergraduates revealed that less than 11 percent reported that their UA classes frequently contained material about or by women. Because of the small number of Women’s Studies faculty and the small number of women hired each year, the paucity of materials on women was unlikely to change without active intervention. In 1980, Women’s Studies leaders decided to begin working with faculty across the university:

One of the most exciting challenges facing women’s studies in the next few years is to integrate the new scholarship on women into the traditional curriculum. Up to the present, most non-Women’s Studies courses have virtually no materials on women. As a result, the majority of students at the University of Arizona graduate without any knowledge of the female experience and perspective. Curriculum reforms which reflect the new scholarship on women are even more critical now when university graduates find themselves in a world where increasing numbers of women are in the labor market and role expectations for both sexes are shifting. Another important area for curriculum reform is the graduate level. With the exception of the English department, no department offers a graduate course in Women’s Studies.[xiii]

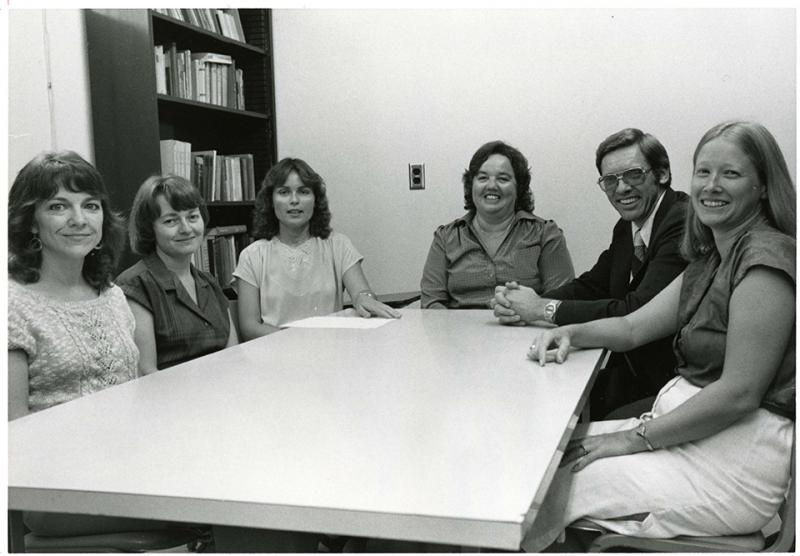

National Endowment for the Humanities Curriculum Project, 1984. Seated left to right: Susan Aiken, Karen Anderson, Judy Nolte Lensink (Temple), Myra Dinnerstein, Jerrold Hogle, Patricia MacCorquodale. UA Communications Records, UA Libraries, Special Collections

In 1981, the Women's Studies program joined a growing national movement to integrate scholarship on women into the curriculum. This project, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, introduced 45 faculty from 13 departments to women's studies scholarship with the intention that they would modify their courses to include this material. Taking an early, national leadership role, Women’s Studies organized a meeting of curriculum integration leaders at Princeton, New Jersey, in the summer of 1981 to consider future directions. The first project became a national model for other projects with the publication of Changing Our Minds: Feminist Transformations of Knowledge.[xiv]

After the first curriculum integration project, Women’s Studies expanded its activities to many multi-year projects with different emphases:

- Western States project focused on four year colleges and universities in sixteen western states.

- International studies project focused on 7 colleges and universities in Arizona and Colorado

- Middle Eastern Studies and Arabic project working with 30 faculty in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah and teachers of Arabic from western states.

- Minority women project based in 7 colleges and universities in Arizona and Colorado

Women’s Studies librarians had a significant role in curriculum integration efforts and advancing new scholarship on women.[xv] Ruth Dickstein at the UA served on women’s studies committees, came to faculty meetings, represented women’s issues on university committees, and was a women’s studies scholar in library studies. With co-authors Victoria Mills and Ellen Waite, Dickstein wrote Women in LC's Terms: A Thesaurus of Library of Congress Subject Headings Relating to Women, published in 1988.[xvi]

The work of Women’s Studies scholars on campus was enhanced from 1988 to 1993 by the Rockefeller Foundation Fellowships in the Humanities. The first three years focused on experiences of women internationally looking at culture, historical, economic and political circumstances. The second three years focused connections between gender and other systems of difference (race, class, ethnicity, age, sexualities).

__________________________________________________________________