Women's Voices & the Vote

"'You're not welcome here because you don't have the proper ID,'" Laughter said the election official told her. "I was so humiliated. It was like I didn't even exist. I raise my thumb today to tell you my thumbprint is who I will always be. Nobody can take that away from me." Agnes Laughter[i]

While Arizona suffragists were celebrating the vote, many women were not empowered by the suffrage legislation. Not all voices were heard in this movement. Women of color struggled to gain the vote for decades after white women gained suffrage. Citizenship has always been controversial in the United States. Lawmakers have limited voting rights by using race, ethnicity, education, and national origin as criteria for citizenship.

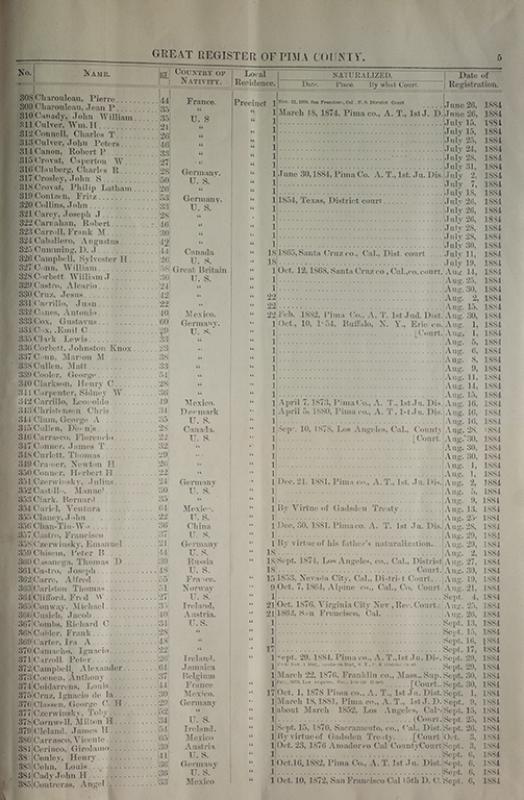

There is a long history of conflict between the U.S. and Mexico over the land that became the Arizona territory. As the Arizona territory was formed and talks about statehood began, people debated citizenship and national origin. Should people of Mexican descent be able to vote? Arizona suffragists were divided over whether and how to reach out the Mexican community.[ii] Many Arizonans focused the concept of citizen on national origin, that is whether someone was native born or foreign born. The Great Register of Pima County of 1884 documents how foreign-born men gained citizenship, for example, through the Gadsen purchase, parent's naturalization, or passing citizenship examination themselves. The 1910 census did not ask people to identify themselves as Mexican, but it did ask about their place of birth and their parents’. One-third of those responding as “white” were born in Mexico or had parents born in Mexico. Some suffragists in Arizona and nationally argued for women’s suffrage because white women’s vote would dilute the influence of foreign-born men. William Herring, President of the 1891 constitutional convention, argued in support of woman’s suffrage because it would “offset the ignorant Mexican vote.”[iii] This argument equates white with native born. Others claimed that white women deserved the vote more than foreign born men. This argument implied that those born in the U.S. were better citizens, perhaps more loyal, informed or aligned with U.S. values, than those born elsewhere.

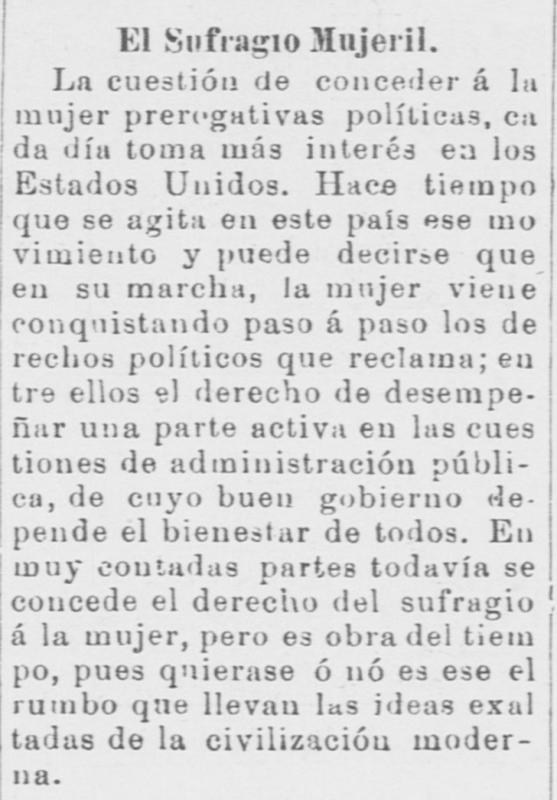

On the other hand, many Arizonans had family members and neighbors of Mexican descent. Arizona suffragists met with prominent members of the Mexican business and political community, held meetings in their homes, and published suffrage material in Spanish. In Tucson, Dr. Rosa Goodrich Boido was president of the Pima County Equal Suffrage Club. Her husband Lorenzo was the leader of La Liga Protectora Latina, a benevolent society that likely co-sponsored suffrage meetings. The leaders of the Arizona Equal Suffrage Association worked with Mexican organizations, Spanish language newspapers, and immigrant miners.

Column supporting women's suffrage from the Tucson newspaper, El Fronterizo, August 15, 1896. Historic Mexican & Mexican American Press Digital Collection, UA Libraries.

Politicians decided to use education as a criterion for citizenship to restrict voting of many Arizonans of Mexican heritage. Advocates of this position argued that democracy depended on educated citizens who could understand issues and candidates’ positions. They decided to use literacy (in English) as a criterion for voting, ignoring the education provided by Spanish language newspapers and schools. In 1909, the Arizona Territorial Legislature enacted a literacy test that required male voters to be able to read the U.S. Constitution in English “in such a manner as to show he is neither prompted nor reciting from memory” and to write his name.[iv] Legislators passed a similar law in 1912 shortly after Arizona became a state. The passage of the 1912 literacy test reduced the eligible Mexican voters by one-third so that they were only 13 percent of registered voters.

Industrialists brought Chinese laborers to work on the railroads and in the mines of the west, but they certainly didn’t see them as citizens. They passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to explicitly prohibit Chinese laborers from becoming citizens. Chinese women and men could not vote until 1943 when the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed after a long battle. Similarly, immigrants from the Philippines and India won voting rights in 1946; Japanese and other Asian immigrants gained suffrage with the passage of the 1952 Immigration Act.

Tohono O'odham registering to vote at Southside Presbyterian Church, Tucson, Ariz. July 28, 1948. UA Libraries, Special Collections

Native people had a different relationship to citizenship than anyone else.[v] Because Native people were defined as citizens of their Native nation and not of the United States, they were not able to vote until 1924 when they were granted dual citizenship. Officials also used Arizona’s literacy law to keep Native people from voting; for example, in the 1910 census, 68 percent of the Indian men and 78 percent of the Indian women were counted as illiterate. Native activists fought against other significant barriers to voting rights, such as acceptable forms of identification, transportation issues, and access to polling places.[vi]

Frank Harrison and Harry Austin, World War II veterans and members of the Yavapai Tribe at Fort McDowell, won a milestone case in 1948. They sued the Maricopa County Recorder for refusing to allow them to register to vote. Judge Levi S. Udall ruled in their favor: “To deny the right to vote, where one is legally entitled to do so, is to do violence to the principles of freedom and equality.”[vii] The Civil Rights Voting Act of 1965 was another important victory that made other strategies for suppressing the Native vote illegal. In 2006, Agnes Laughter, a Diné elder, challenged the 2004 law that limited the kinds of identification that could be used when voting; she argued that getting the acceptable forms of identification impeded her right to vote given her available transportation and the distances on the Diné nation.[viii] The Department of Justice settled the case two years later by expanding the acceptable forms of identification. Native leaders successfully introduced the Native American Voting Rights Act in 2018 and 2019, but they did not get enough support to proceed to a vote in Congress.

Another key issue for Native voting is how the legislative districts are drawn. Gerrymandering is the practice of drawing district lines to favor the interests of particular groups or political parties. People of color fought against gerrymandering in many geographical regions because they wanted sufficient numbers in their district to have a chance of electing representatives from their groups, neighborhoods, and families. Proposals by the Navajo Nation, with 332,129 enrolled members, can be compared to see how the district lines can affect the representation of different groups in a particular region.[ix]

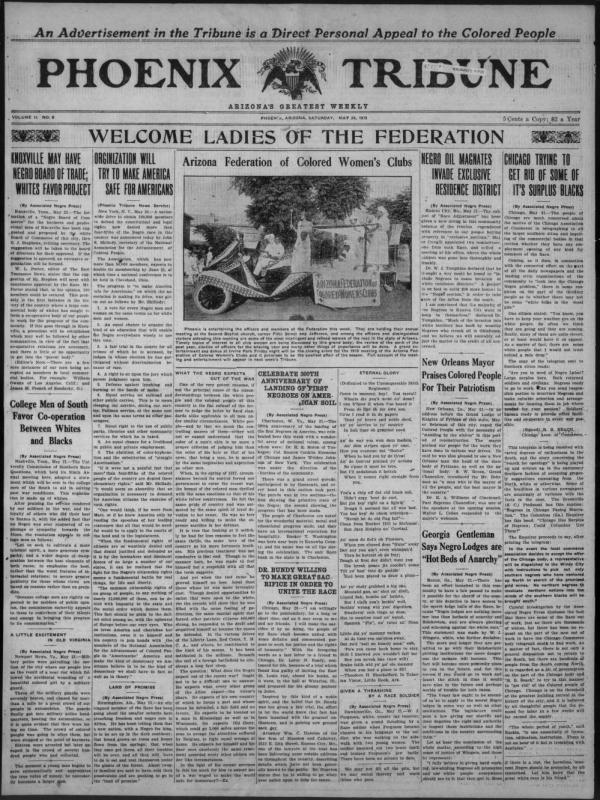

Arizona Federation of Colored Women's Club, courtesy of Los Angeles Public Library

Phoenix Tribune, May 24th 1919. Chronicling America

Suffragists’ racism was evident when they asked African American[x] women to march at the back of national parades and focused on white women in some state-by-state suffrage campaigns. Arizona suffragists also ignored African American women, in part, because of their small numbers. In 1880 there were only 155 African Americans in Arizona out of 40,340 residents (.38 percent), and in 1910, 2009 out of 204,354 residents (.98 percent). In other states, African American women worked for suffrage through the National Federation of Afro-American Women, the National Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, and the National Association of Colored Women. In 1915, African American women organized the Arizona Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs in Phoenix to fight for equal rights.

Although women of color faced obstacles to voting, a few Mexican and African American women registered to vote in Pima County in 1913.[xi] Mexican women were identified by their birthplace, family names, and family histories. This analysis found 18 women (three percent) of Mexican heritage who registered compared to the population rate of 25 to 35 percent. The registration process identified "colored" women by asking about race; five women identified as "colored" when registering, and two others were listed as "colored" or "mulatto" in the U.S. Census. This registration rate of one percent is equivalent to African American women’s representation in the 1910 census. No Native women were allowed to register to vote.

The concept of “citizen” has been built upon contested ideas about race, ethnicity, and national origin. People need to be vigilant and eliminate barriers to voting that restrict the voices of citizens across racial, ethnic, and national groups.

__________________________________________________________________