The Afterlife of the Reformation, 16th to 21st Century

The Protestant Reformation is alleged to have shaped major features of Western culture, including freedom of religion, freedom of conscience, the dignity of the individual, and political democracy.

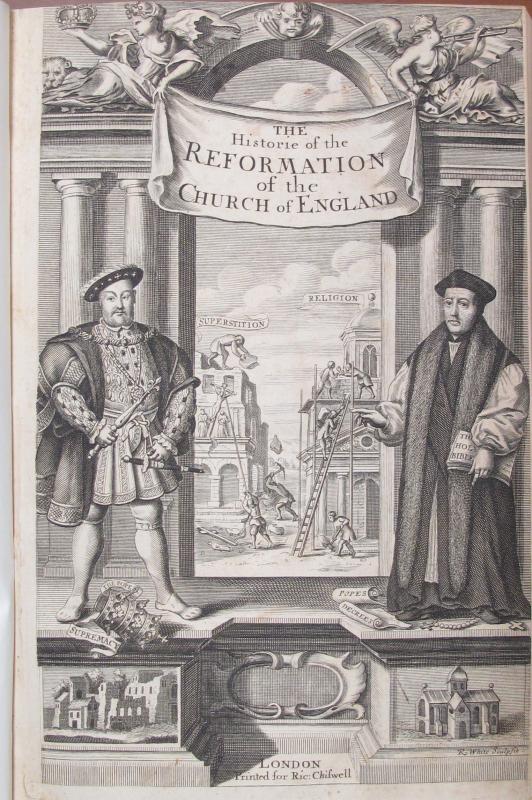

The Protestant Reformation did not have one, but many afterlives. And it has fundamentally shaped the history of the centuries following it up until our own time. Even in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, during the age of confessional conflicts when the Catholic church and different Protestant churches in Europe fought for the hearts and minds of the people, histories of the Reformation were already written and conflicting interpretations offered. In martyrologies and historical accounts of both medieval and recent history, Reformation and Counter-Reformation scholars and polemicists sought to shape a view of the events of the Protestant Reformation that could be used as propaganda for their own side and shape their communities' identities.

As time progressed, "The Reformation" came to be seen as a coherent sequence of events which was described, until the twentieth century, in positive terms by Protestant historians and in negative terms by Catholic ones. In Britain, the so-called "Whig history" saw the English Reformation as an integral part of the success story of the nation. Parliament, a constitutional monarchy, economic success culminating in the industrial revolution, and Protestantism were bound together into a triumphant story in which England was the paragon of freedom and progress. In Germany, nineteenth-century historiography was confessionally split, but dominated by Protestant historians, mostly in Prussia, who tended to see the Reformation as the beginning of the modern age.

The thoughts of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth scholars like Ernst Troeltsch and Max Weber have deeply influenced the perception of the Protestant Reformation. While Troeltsch regarded the mainstream Reformers as still medieval, he argued that modernity was ushered in by Protestant sects like the Anabaptists. Max Weber's saw the Reformation as a major turning point in the "disenchantment of the world," and he claimed an association between the concept of predestination in Calvinism and the development of modern capitalism. In Weber's view, the Calvinist doctrine of "double predestination" led to the "Protestant work ethic" because believers used their worldly success to confirm in their own minds that they were saved (predestined by God to heaven). This Protestant work ethic then led, according to Weber, to the development of capitalism. The economic success of the early modern Netherlands, where the Calvinist church was the "public church," has often been cited as an example in this context. Weber's theory has been thoroughly debunked by historians, but it continues to be a powerful idea to this day.

Overall, this raises the question how to identify and describe the formative long-term influences of the Protestant Reformation on the Western world more generally and on American history in particular. The American public retains a sense of relatedness to the Puritans of Massachusetts, who were products of the English Reformation as a powerful movement, and Americanists have claimed that without the New England Puritan regime in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, our nation would have a different cast of mind.

Early printed books in the Heiko A. Oberman Library at the University of Arizona : with an appendix Selected Recent Acquisitions ; Carl T. Berkhout.

The Protestant Reformation is on the one hand alleged to have shaped major features of Western culture, including freedom of religion, freedom of conscience, the dignity of the individual, and political democracy. On the other hand, scholars have claimed that the Reformation and the resulting divisions in Western Christianity are responsible for a secular society based on a harsh capitalist economy in which community values are underrated and individualism is overrated. These remain matters of deep concern to modern Americans. Did the Reformation produce or influence them? Historians will continue to debate these questions because the relationship between cause and effect is hard to prove over a period of five centuries.

There can be no doubt, however, that the Reformation has many afterlives. Above all, it has resulted in the creation of many different Protestant faiths and churches around the world. Today, Protestantism is expanding in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, while continuing to have a strong presence in Europe and North America. Soon, Europeans and people of European descent will no longer form the majority of Protestants. This raises the question of what types of connections, if any, can be identified between the origins of a religious movement and the various manifestations of this religious movement as it adapts to different cultures over the course of five centuries.

However, there can be no doubt that in terms of identity, these connections are strong. The many events, websites, activities, and books generated by the five hundredth anniversary of the Protestant Reformation certainly prove that this event continues to have an important place both as part of the scholarly enterprise as well as in the popular imagination.

To cite text:

Karant-Nunn, Susan, & Lotz-Heumann, Ute (2017). Confessional Conflict. After 500 Years: Print and Propaganda in the Protestant Reformation. University of Arizona Libraries.

Selected titles from University of Arizona Special Collections:

Johann Sleidan (1506-1556). Commentariorum, Strasbourg, ca.1500?

Philipp Saltzmann, Singularia Lutheri, Naumburg, 1664

Gottfried Weyer (1610-16 82). Ephemerides, Cologne, 1679

Gilbert Burnet (1643-1715). Historie van de reformatie, Amsterdam, 1686

Snyod of Dort (1618-1619). Acta Synodi nationalis, Dordrecht, 1620

Schriftelicke conferentie, The Hague, 1612